What is social engineering? A complete security guide

Not every cyberattack starts with a technical exploit or malicious download. Many begin with seemingly harmless interactions, such as a delivery text, an email from the IT team, or a quick call asking you to confirm account details. Rather than trying to force entry through infected software or device vulnerabilities, social engineering aims to trick users into giving attackers access to sensitive accounts and/or data.

This article explains what social engineering is, how it works, the main types to watch out for, and the psychology behind it. It also covers what to do if you ever fall victim to a social engineering attack.

What does social engineering mean?

In cybersecurity, social engineering refers to the use of deception and persuasion to make someone do something that compromises security, such as revealing a password, granting access to a restricted system, or clicking a malicious link.

What sets social engineering apart is its method. Instead of exploiting code or hardware, attackers exploit human behavior by using trust, curiosity, or fear to make a communication appear legitimate. It can take many forms, such as a phishing email, a fake support request, or a call that seems to come from a trusted organization.

Attackers often reach out through familiar channels, like email, text, phone, or chat. Their messages are designed to feel natural and relevant, so they blend into your routine.

The danger is that one convincing message can undo years of investment in security. Firewalls and encryption offer little protection if an attacker gains access because someone trusted the wrong request.

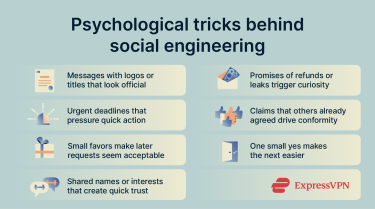

The psychology behind social engineering

Social engineering works because it exploits the mental shortcuts people use to make quick decisions. In short, attackers take advantage of how we naturally respond. When something appears to come from an authority figure or references a familiar situation, we’re more likely to click without verifying it.

- Authority: Messages that appear to come from a department head or government office often go unquestioned.

- Urgency: Deadlines like “act now or lose access” push people to react before verifying.

- Reciprocity: After offering help, an attacker might ask for remote access. Because they appeared helpful at first, the request feels like a fair exchange.

- Familiarity and liking: Mentioning a coworker or shared interest can make a stranger seem trustworthy. Attackers can also craft emails to be visually pleasing to their target, increasing the chance they will engage.

- Curiosity: Unexpected refunds, leaked files, or exclusive offers exploit the urge to look.

- Social proof: When something seems endorsed or widely accepted, people are more likely to comply.

- Commitment: Agreeing to a small request increases the chance of saying yes to a riskier one later.

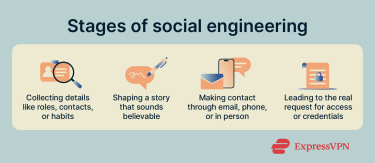

How social engineering works

Social engineering usually unfolds across several stages that aim to produce a specific outcome.

The first stage is information gathering. Attackers collect background details that help them appear credible. Those facts are rarely valuable on their own, but they let an attacker shape a believable story.

That story, often called a pretext, gives the attacker a reason to get in touch. The pretext is sent through whatever familiar channel the target is most likely to accept. Early contact is usually low-risk and routine in tone so the target feels comfortable.

The final stage is the request. After the groundwork is laid, the attacker asks for something valuable, such as credentials, approval, or access. Success can depend on how convincing the earlier steps were and whether the request is accepted without additional verification.

The tactics attackers use

Different campaigns use different methods, but tactics like pretexting, impersonation, and malware delivery appear often in real-world incidents.

- Impersonation and spoofing: Attempts to imitate trusted sources to trick people into trusting a message.

- Channel switching: Attackers may use multiple forms of contact to make a story feel more convincing.

- Malware delivery: Malicious software can be delivered via attachments or links, allowing attackers to compromise devices or data.

- Multi-factor fatigue: Repeated authentication requests can wear people down and increase the chance of approval.

- Physical infiltration: Gaining unauthorized physical access by posing as a legitimate visitor or worker.

Examples of social engineering attacks

There are plenty of well-documented cases that have used social engineering. These attacks involved impersonation of famous people on social media to exploit trust and reach as many of their followers for monetary gain, or tricking employees into wiring money into attacker-controlled accounts. Phishing emails with malicious attachments have also been used to successfully compromise large companies and gain access to sensitive data.

It’s important to note that such attacks don’t only target high-profile individuals and companies; everyday users are also at risk. Many attackers target older adults, as they believe they have more money in the bank than someone younger.

Common forms of social engineering attacks

Social engineering is a broad category, and attackers adapt their methods to each situation. The same person might send a convincing email in one case and make a phone call or visit in another, depending on what the target is most likely to trust.

What all these attacks share is their focus on manipulating people rather than exploiting technology. Below are some of the most common forms, each with its own approach and impact.

Phishing and spear phishing

Phishing is a form of fraud where attackers send messages that look legitimate in order to trick people into taking harmful actions. Such attacks can occur over a wide variety of channels, including email, social media platforms, and web forms.

These messages often mimic trusted organizations such as banks, online stores, delivery services, or internal departments like HR. They typically contain a link or file designed to capture information or compromise a device. Usually, the goal is to steal data, credentials, and/or install malware.

Phishing campaigns vary widely in scale and sophistication. Some are broad and automated, reaching large numbers of people in hopes that a few will respond. Others are more focused and carefully written to increase their chances of success. The latter is referred to as spear phishing.

In spear phishing, the attacker researches a specific person or small group to make the message feel authentic. It may reference familiar details to make a message feel credible. When a message matches the target’s reality, it becomes much harder to recognise as fraudulent.

Smishing and vishing

Smishing uses text messages or chat apps to trick people into taking action. The victim may receive a message claiming that a package is waiting for confirmation or that a bank account needs urgent attention, pushing the recipient to click a malicious link.

Vishing is conducted by phone. Attackers call while pretending to be from trusted organizations such as banks, IT support, or government offices. Caller ID spoofing makes the call look real, and urgency is often used to pressure the victim into revealing information such as one-time passcodes or account details.

Baiting and quid pro quo

Baiting tempts a target with something appealing to make them act. The lure can be physical, such as a USB drive left where an employee might find it, or digital, like a malicious download or a fake prize link. The result can be malware, stolen files, or the creation of a hidden access point for later attacks.

Quid pro quo scams work as a simple trade. An attacker offers a benefit, such as tech support, a refund, or a promised service, in exchange for a small action like sharing a code, running a command, or giving a password. Framed as a transaction, they sound reasonable, which is why training and verification procedures are important.

Tailgating and piggybacking

Tailgating happens when an intruder enters a restricted area right after an employee, taking advantage of the fact that the door is already open. Piggybacking is slightly different: the employee actively lets someone through. This can happen when the intruder looks like a delivery driver, appears to be carrying equipment, or claims to have misplaced their badge.

In either case, the attacker avoids the credential check and gains physical access to spaces meant to be restricted. Once inside, they can sit at a workstation, copy files, or connect rogue hardware without attracting attention. These tailgating and physical access breaches bypass digital defenses entirely.

Watering hole attacks

In watering hole attacks, the attacker doesn’t target individual victims. Instead, they compromise a website that a target group already visits: an industry portal, a professional forum, sometimes even a supplier’s site. Visitors pick up malware or get pushed to a fake login page while thinking they’re on trusted ground.

Scareware and malware delivery

Scareware often arrives in the form of fake system alerts that make claims like “Your PC is infected” or “Personal data exposed.” The supposed fix is malicious in nature; for example, a download that contains malware.

Business email compromise

Attackers send an email that looks like it came from a CEO, a partner company, or a supplier. The message asks for a wire transfer or sensitive records, and because it comes from what appears to be a trusted sender, people comply. No links, no attachments; just authority and timing. Losses from these scams are in the billions worldwide.

How to recognize social engineering attempts

Recognizing social engineering attempts means paying attention to details or behaviors that don’t match what you’d normally expect.

Warning signs to look out for

- Time pressure: Messages that demand quick action or threaten consequences, especially in relation to money, credentials, or access, are red flags.

- Full credential requests: Legitimate organizations will never ask for complete passwords, multi-factor authentication (MFA) codes, or full payment details by email, text, or phone.

- Unexpected contact: Treat any out-of-the-blue message requesting sensitive information with caution, even if it mentions a known company or colleague.

- Breaks in routine: Be wary of sudden changes in how payments, approvals, or requests are handled.

- Personal detail misuse: Attackers may include accurate names or roles to sound credible. The giveaway is when those details appear in contexts that don’t fit.

- Language quality: Typos, awkward phrasing, or unnatural tone can still mean a scam, though many attackers now use tools that make messages look polished. Always consider whether the writing style matches what you normally see from that sender.

- AI-driven realism. AI-generated text and voices can often be very believable. Authenticity of a message or call depends on the timing of the communication, the channel used, and behavior, not how real it sounds.

Common red flags in emails, calls, and links

Emails

Attackers may alter a real domain by a single character, such as micros0ft.com. Checking the full email header can reveal if a message claiming to be from a company like PayPal was actually sent from a scammer.

Be cautious with attachments, too. A file that looks harmless, such as an invoice or report, can contain hidden code, and clickable buttons or images may lead to unsafe sites.

If an attachment is unexpected, stop and check whether it makes sense based on your recent activity before opening it. Even then, confirm the address it was sent from and if possible, contact the sender on a separate channel to confirm the attachment.

Calls

Caller ID on its own is unreliable. Numbers can be spoofed so they appear to match a bank, government office, or internal extension. Some scams also stitch together background noise or hold music to sound more convincing. A call becomes suspect when it introduces requests that wouldn’t normally be handled over the phone, such as changes to account access or the authorization of financial transfers.

Links

A visible link can hide its true destination. The text may appear legitimate while the underlying address points somewhere else. Before clicking, check where it actually leads by pressing and holding the link on mobile or by hovering over it with your mouse on desktop.

Subtle changes in domains, long redirect chains, or shortened URLs are all techniques used to disguise the real destination. HTTPS and the padlock icon only show that the connection is encrypted, not that the site itself is trustworthy. Many fraudulent sites now use HTTPS, so it’s still important to check the actual domain name. In some campaigns, attackers go further with browser-in-the-browser pages that generate fake login windows inside a site.

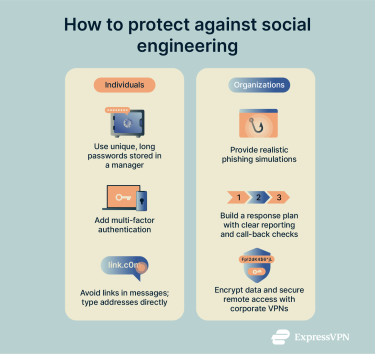

How to protect yourself from social engineering

Protecting from social engineering attacks means combining personal vigilance with company-wide measures.

Best practices for individuals

Strengthen your password security

The simplest way to reduce social engineering risk is to avoid using the same password in more than one place. A breach at a single service often leads to attackers testing the same login on others. Passwords are most secure when they are at least 12 characters long and unique. A password manager can help you when it comes to remembering them all, and some even flag if a saved password has already appeared in a public breach.

ExpressVPN Keys is one example of a password manager that can store unique passwords and alert you if any are found in known breaches.

Use multi-factor authentication (MFA)

Adding a second authentication factor (whether that’s a code from an authenticator app or a fingerprint) makes account takeover far harder. SMS codes are better than nothing, but they can be intercepted or redirected, which is why app-based codes or physical keys are considered stronger options.

Stay alert to phishing attempts

Build habits that reduce the chance of mistakes. Go directly to websites by typing the address or using bookmarks instead of clicking links in emails or messages. A password manager adds protection by only autofilling credentials on the exact site where they were saved. If it doesn’t prompt you to log in, take that as a warning. Also limit how much personal information you share online, as attackers can use those details to craft convincing lures.

Protection for businesses and organizations

Implementing employee training

Regular cybersecurity awareness training helps employees recognize suspicious messages in realistic situations. Many organizations use phishing simulations or scenario-based exercises to give staff hands-on practice.

Not every employee needs the same level of training, however. People who handle payments or manage executive accounts are targeted more often and should see tailored scenarios.

Training also has to keep pace with new tactics. Well-written phishing emails and even cloned voices are already being used in attacks. Tracking how staff respond over time (who reports, who ignores, who clicks) gives security teams a clearer picture of whether awareness is improving.

Company programs can also be tied into broader initiatives like Cybersecurity Awareness Month, which highlight the human side of security and encourage continuous learning.

Building a response plan

An effective response plan makes it clear who reports incidents, who leads the investigation, and how compromised accounts or devices will be isolated. When a breach or suspicious activity is detected, the first priority is to contain the situation before it spreads.

This usually means temporarily restricting access to the systems or data that may be affected, so only the people directly involved in the response can reach them. If unauthorized access involves an employee account, passwords should be reset and access re-authenticated before normal permissions are restored.

At the same time, logs and monitoring data should be reviewed to understand what was accessed and how far the incident reached. This early scoping step guides the rest of the response, including whether notifications, forensic support, or recovery efforts are required.

The goal is to act quickly and deliberately, so the organization isn’t making decisions under pressure or losing time to uncertainty.

Using VPNs and encryption tools

Technical safeguards should ensure that if data is intercepted or copied, it cannot be easily used.

A VPN adds protection for remote connections by encrypting internet traffic, helping keep information private on public or shared Wi-Fi.

For businesses, a corporate VPN also allows employees to securely access internal company resources from outside the office. By contrast, commercial VPNs (like ExpressVPN) protect individuals’ data and privacy online but don’t provide remote access to private networks.

Encryption should also apply to stored data. This is typically done by enabling full-disk encryption on company devices and using built-in encryption settings in the services that store files and email. If a laptop is stolen or a mailbox is copied, the information is more likely to remain unreadable without the decryption keys. Network monitoring tools can alert administrators to unusual login attempts or access from unexpected locations, too.

Combined with access controls that limit what each employee can see or change, these measures restrict how far an attacker can go even if a single account is compromised.

FAQ: Common questions about social engineering

What is an example of social engineering?

A common example is phishing, where an attacker sends an email that looks like it comes from a trusted source such as a bank or service provider. The message usually asks the recipient to click a malicious link or share credentials.

What are the main types of social engineering?

The main types include phishing and spear phishing, smishing and vishing, baiting, and quid pro quo scams. Each works differently, but all rely on manipulating people instead of exploiting vulnerabilities in devices or networks.

How can organizations prevent social engineering attacks?

Organizations can reduce risk by combining employee awareness training, strong access controls such as multi-factor authentication (MFA), and clear response plans. Technical measures like email filtering and encryption help, but the most important factor is preparing staff to spot and report suspicious activity.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN